How to teach adolescents to read long words

Reading long words: A common problem for secondary school pupils

It’s common to come across secondary school students who are pretty good at decoding one- and two-syllable words, but will guess longer words based on a few letters or the first syllable. For example, they might read complicate as complain, or triumphant as trumpet. Guessing can be fairly successful at primary school, where the vocabulary is simpler, and there are likely to be pictures that can act as prompts to help guess the words. But at secondary school the texts are more complex, and these students can find themselves floundering in a sea of long words.

Such students need strategies for dividing long words into chunks that they can decode individually, and then join back together to make a whole word. It sounds easy, but this process requires a surprising amount of knowledge on the part of students. In this blog post, I discuss different approaches to chunking long words, the knowledge that is required to do this successfully, and the implications for teaching.

I’ve split this post into three sections as follows:

Section 1: Two approaches to chunking long words, and why they are both needed

Section 2: What do students need to know to break words into chunks successfully?

Section 3: What are the implications for how we teach students to read long words?

Section 1: Two approaches to chunking long words, and why they are both needed

Why do long words need a different approach to short words?

When we learn to decode a short word such as dream, we break it down into individual letters or letter sequences called graphemes (<d> <r> <ea> <m>). These graphemes are matched with individual sounds called phonemes (/d/ /r/ /ē/ /m/), and then the phonemes are blended together in sequence as we pronounce the word “dream”.

Over time, we learn to recognise these words automatically rather than having to break them down and analyse them every time. However, when we encounter unfamiliar short words, we still segment words into graphemes, match them to phonemes, and then blend together the phonemes.

But for unfamiliar long words, breaking words down into a sequence of graphemes and their associated phonemes doesn’t work. This is because our working memory (our ‘mental workspace’) is limited, and there are simply too many sounds to hold in memory at once.

So, to decode long words, we need an intermediate step. We need to break words down into manageable chunks, decode each chunk by segmentation and blending, and then put the chunks back together to build the word.

Two approaches to dividing long words into chunks

There are two main approaches that are helpful for dividing unfamiliar long words into manageable chunks:

Words can be broken into syllables by marking in syllable boundaries. For example, interruption could be broken into the following syllables: in/ter/rup/tion.

Words can be divided according to their morphological structure. That is, they can be broken into meaningful word-parts called morphemes. Morphemes can be prefixes (which join on the start of words), bases (which carry the main meaning of the word, and are also sometimes called roots), or suffixes (which join onto the end of words). A word that has been broken down into morphemes can be written as a word sum. For example: inter + rupt + ion —> interruption

Below, I outline the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, before explaining why I think both approaches are needed.

Strengths and weaknesses of each approach

Breaking words into syllables

Strengths

Marking syllable boundaries in a written word will usually align with spoken syllables, helping students to figure out the word’s pronunciation e.g. i/den/ti/fi/ca/tion

Marking syllable boundaries breaks the whole written word into small chunks that the student should be able to decode e.g. un/sen/ti/men/tal

Weaknesses

Syllabification does not generally provide helpful insights into a word’s meaning.

It’s not always obvious how to pronounce syllables. For example, the student needs to know that <tious> in infectious is pronounced as “shuss”.

Written syllables do not always correspond to spoken syllables. For example:

The written word general would be divided into three separate syllables: gen/er/al or ge/ne/ral. However, it would usually be pronounced with two syllables as “gen-rul”.

In long words, unstressed syllables are often reduced to schwa. (Schwa is the “uh” sound at the start of “about”, and it’s a common sound in English.) For example, in confident, the <e> would usually be pronounced as “uh”.

Knowledge of vowel graphemes and the structure of English syllables is required to successfully divide words into syllables (see also Section 2).

Breaking words into morphemes

Strengths

Morphological structure provides insights into the meaning of words. For example:

The word sum for interruption is: inter + rupt + ion —> interruption

The prefix <inter‑> means ‘between’, <rupt> means ‘break’, and <‑ion> is a noun-forming suffix. Therefore, interruption is a noun that means something that comes between parts of a task or conversation and breaks it up.

Identifying morphemes allows students to make meaningful connections with related words. For example:

The prefix <inter-> occurs in words such as international, interconnected and interactive, which all connect to the meaning ‘between’.

The base <rupt> occurs in related words such as disrupt, erupt and abrupt, which all connect to the meaning ‘break’.

The suffix <-ion> occurs in lots of English words, such as action, discussion and question, and it indicates that a word is a noun.

Weaknesses

Morphological boundaries don’t always align with syllable boundaries, which can make it difficult to go from a word sum to pronouncing a word accurately.

For example, analysing the word interruption as inter + rupt + ion breaks up the letter sequence <tion>, which is pronounced as a single syllable that sounds like “shun”.

Identifying prefixes, bases and suffixes is not always simple because some words don’t have an obvious morphological structure e.g. mannequin, cantankerous, spontaneous.

If students are not familiar with many prefixes and suffixes, they may still be left with a long string of letters to decode. For example:

If a student is trying to read unsentimental and they can only identify the prefix <un‑> and the suffix <‑al>, the resulting word sum is:

un + sentiment + al —> unsentimental

For many students, the letter string <sentiment> is still too long to decode in one chunk.The fully analysed version would be:

un + sent + i + ment + al —> unsentimental

The <i> is a connecting vowel.

This analysis results in nice, small chunks to decode, but it requires a good knowledge of prefixes, suffixes and connecting letters to get there.

Why are both approaches needed?

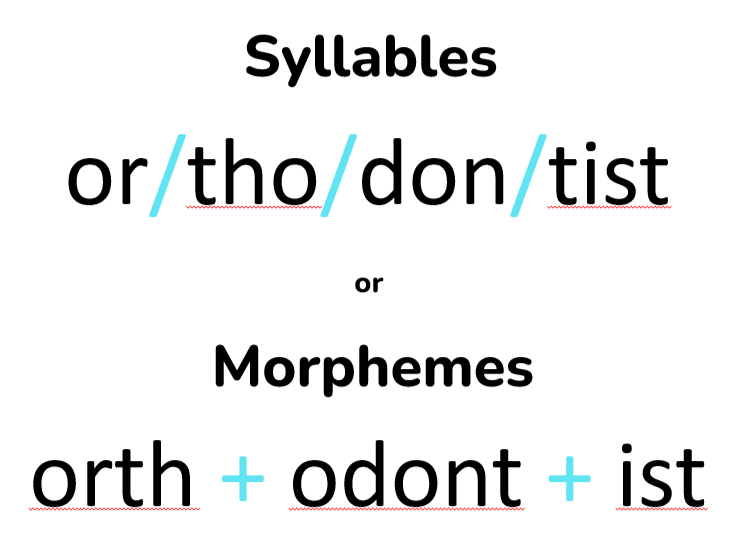

A syllabic approach divides the word ‘orthodontist’ into small chunks that are easy to decode. A morphological approach provides insights into meaning: <orth> means ‘straight’ or ‘correct’, <odont> means ‘tooth’, and <ist> indicates a person doing a job.

So, is a syllabic approach or a morphological approach better? Well, the two approaches have complementary strengths and weaknesses. That is, a syllabic approach will tend to link more closely to pronunciations but provide little insight into meaning, while a morphological approach will provide more insights into meaning but may not intuitively link to pronunciation.

For this reason, I find it helpful to teach students both methods of ‘word attack’. Teaching both approaches means that:

Students can choose the most appropriate approach for the target word.

Students can use a combination of both approaches to maximise their chances of pronouncing and understanding the word correctly.

Let’s look at these two benefits in more detail.

1. Choosing the most appropriate approach for the target word

Generally, I suggest trying a morphological approach first because it will give students some insight into a word’s meaning. If the morphological approach doesn’t work, then students should try syllabification, which may make a more direct link with the pronunciation and help them to recognise the word.

Here are two example target words, together with my suggestions for the best approach to dividing them into chunks:

Example 1: reconstructing

Reconstructing includes some common morphemes, so the student is likely to be able to analyse the word as: re + con + struct + ing

Each morpheme can be easily recognised (or decoded) individually, and then the chunks can be put together to make the word reconstructing. If needed, the meaning can be inferred from the morphemes: <re‑> meaning ‘again’, <con + struct> meaning ‘build’, and <‑ing> meaning ‘an ongoing process’.

In Example 1, the morphological approach works well.

Example 2: mayonnaise

For mayonnaise, there are no obvious prefixes or suffixes, so the morphological approach doesn’t work.

The student should try a syllabic approach instead. This gives: may/on/naise (or something similar).

These syllables can be decoded individually and then sequenced, and the student should arrive at “may – on – naise”, which they may recognise.

In Example 2, the morphological approach doesn’t work, but a syllabic approach is likely to be successful.

As these two examples demonstrate, it’s important to be flexible, and to use the strategy that is most useful for the target word.

2. Combining the two approaches

It’s also possible to combine the syllabic approach and the morphological approach. I like to teach students to circle any morphemes that they identify, and then divide the remaining part of the word into syllables.

So, for unsentimental, the student may end up with a partial morphological analysis that identifies <un‑> and <‑al>, and the rest of the word divided into syllables, as shown here:

This analysis should help the student to identify the word-part sentiment meaning ‘feeling’, and then the full word unsentimental, which is an adjective (signified by the suffix <‑al>) that means ‘without strong feelings’.

The goal is to achieve successful decoding and understanding of the target word, rather than to achieve a comprehensive morphological or syllabic analysis of the target word.

Section 2: What do students need to know in order to chunk long words successfully?

I’ve discussed two approaches that students can use to chunk long words successfully – the syllabic approach and the morphological approach. But if you just dive in and try teach these approaches from a standing start, you’re soon going to hit problems! It turns out that students need to know a lot in order to successfully decode unfamiliar long words. I think the prerequisite knowledge for chunking long words is often underestimated.

So, let’s look in more detail at the precise strategies for chunking words, and consider what students need to know to implement them.

What do students need to know to break long words into syllables effectively?

‘Teaching syllables’ is often done orally, with students learning to break words into ‘beats’ and to count them. As a syllable is a chunk of speech that is centred on a vowel sound, an oral approach to understanding syllables is a good place to start. However, breaking spoken words into syllables is a very different skill from marking syllable boundaries in an unfamiliar written word, and then using these chunks to help with decoding. The steps from one to the other are often not explicitly taught, or are taught using syllable types, which can be unreliable¹.

For syllabification, I teach students to identify and label vowel graphemes, and then place syllable boundaries between successive vowel graphemes to make acceptable English syllables.

However, for this strategy to lead to successful word recognition, students need a surprising amount of prior knowledge. Below I’ve listed some key information that students need to know in order to break an unfamiliar written word into syllables using this strategy.

To break long words into syllables effectively, students need to:

Know that a syllable is a ‘beat’ in a word.

Know that a syllable contains one vowel grapheme.

Know that a vowel grapheme can have one, two, three and (under some analyses) very occasionally even four letters. (You may also like to teach that that a one-letter grapheme is called a unigraph, a two-letter grapheme is called a digraph, and a three-letter grapheme is called a trigraph.)

Know the vowel letters are <a> <e> <i> <o> <u> and sometimes <y>.

Know that most vowel graphemes are spelled with vowel letters, but they may also include consonant letters e.g. <ar> <aw> <igh>.

Recognise most vowel digraphs and trigraphs, and distinguish these from consecutive vowel letters that represent their own sounds.

For example, bean contains a vowel digraph, while li/on is a two-syllable word that has adjacent vowel unigraphs).

Know that syllable boundaries should not separate individual letters within a digraph. For example:

meth/od or me/thod are acceptable ways of dividing the word method.

met/hod does not work because <th> is a single grapheme.

Understand what constitutes an acceptable syllable in English. For example:

contract could be syllabified as con/tract (which also aligns with the morphological boundary) or cont/ract.

contract could not be analysed as contr/act or co/ntract because <contr> and <ntract> are not acceptable syllables in English.

Recognise when final <e> counts as separate vowel grapheme and when it doesn’t. For example:

For confuse, the final <e> is part of a split digraph <u_e> representing the phoneme /ū/, so it shouldn’t be placed in a separate syllable.

The final <e> in grumble does necessitate another syllable, as it is part of what is often called a ‘Consonant plus <le>’ syllable.

Be able to pronounce syllables with unusual grapheme-phoneme correspondences such as <tion> <tious> <ture> <cial>.

What do students need to know to use a morphological strategy effectively?

There are different ‘levels’ of knowledge when it comes to morphology. Students can either just ‘peel off’ the most obvious affixes and then decode whatever remains, or they can do a complete morphological analysis that may include less obvious affixes, connecting letters, and changes due to suffixing conventions.

For a morphological approach to be most effective, students need to:

Know the terms prefix, base (or root, or whatever equivalent term you use) and suffix.

Be able to recognise a lot of prefixes and suffixes – it also helps to recognise a lot of bases.

Know the meaning or role of many prefixes and suffixes.

Know that connecting vowel letters may be used to link morphemes. For example:

hydr + o + gen —> hydrogen

Know that the base may look different when suffixes are added. For example:

Drop <e> convention e.g. fame/ + ous —> famous

<y> to <i> convention e.g. cry/i + ed —> cried

Doubling convention e.g. tap(p) + ing —> tapping

And that’s not all they need to know…

Even when a word has been successfully broken into either syllables or morphemes, or a combination of the two, students need more knowledge and skills to accurately recognise and understand the word.

Firstly, students need to be able to ‘flex’ graphemes because some graphemes have more than one possible pronunciation. For example, rapid could be pronounced as with a long /ā/ (like “raypid”) or a short /ă/ (like “rappid”). To recognise a word, students may need to try out alternative pronunciations of graphemes – which obviously means they need to know the possible pronunciations.

In addition to all of the above, students need to be able to decode the individual syllables/morphemes, hold them in their mind, and then add them all together and to create a word. Pupils with poor working memory may need a strategy for gradually building the word by adding only one syllable or morpheme at a time. For example, interruption would be built as “in … in-ter … in-ter-rup … in-ter-rup-tion”.

And finally, there’s another step: students need to recognise the word! For this, they need a good knowledge of vocabulary.

No wonder lots of students find it difficult to read unfamiliar long words!

Section 3: What are the implications for how we teach students to read long words?

When you realise how much students need to know to tackle long words, it can feel a pretty daunting thing to teach, and it may be hard to know where to start!

Although there are some students who will ‘take to’ reading long words with ease and won’t need explicit instruction, most students will benefit from explicit instruction in the syllabic approach and the morphological approach outlined above, and some students will be lost without it. But these approaches only work in the context of a student’s wider knowledge. If the foundational knowledge and skills aren’t there, students will be unable to complete the steps that are needed to chunk a word, decode the chunks, rebuild it, pronounce it, and recognise it.

So, exactly how much do students need to know before you teach the strategies?

Well, it’s not an all-or-nothing answer. For example, you can introduce the idea of syllabification by inserting the syllable boundaries yourself if the student is not at a stage where they can do that for themselves. Similarly, as soon as students know one or two prefixes or suffixes, they can start spotting them in target words. For older students, if we wait until every grapheme-phoneme correspondence is taught, and all the suffixing conventions are memorised, we will be waiting too long. So, breaking words into manageable chunks can be modelled and scaffolded by the teacher from an early stage.

However, in order to ensure that students learn everything they need to know to decode long words independently, I advocate combining this with a structured approach, as described below:

Begin by assessing students so that you can find the gaps in their knowledge. For example, in Section 2, I mentioned that students need to know lots of vowel digraphs and trigraphs in order to accurately insert syllable boundaries. If your assessment shows that students don’t know enough grapheme-phoneme correspondences, they need to learn them as part of a systematic phonics intervention. Similarly, to flex the pronunciation of graphemes, students need to be confident of the ‘pronunciation options’ for each grapheme.

To teach concepts and terminology, I suggest using a structured programme. Concepts and terms should be introduced gradually to avoid overwhelming students, but the pace can be adjusted depending on their prior knowledge. For example, if students already know the vowel letters, there’s no point spending time teaching them, and you can move straight on to the next topic; if students don’t know vowel letters, you can use several activities to practise them, and take plenty of opportunities to review them.

Use targeted activities to explicitly teach syllabic and morphological approaches for decoding long words, and how to combine these approaches, and also practise vowel flexing to achieve the correct pronunciation. The syllabic and morphological approaches should be taught as specific strategies:

For syllabification, it will involve labelling the vowel graphemes and then marking syllable boundaries to create acceptable syllables in English.

For a morphological approach, it may involve circling prefixes and suffixes, or writing the word as a word sum.

I tend to use these targeted activities after introducing most of the concepts and terminology.

It’s also important that students develop reading fluency, so that they can automatically recognise long words. To develop fluency, students need lots of reading practice, so the structured approach described above should be supplemented by students reading texts that include long words. Ideally, students should have feedback when decoding and understanding unfamiliar long words, and then have the opportunity to re-read the text to consolidate their learning².

This reading practice is also essential for developing vocabulary knowledge that will feed back into improved accuracy for reading long words.

Summary

To summarise, teaching students specific strategies for chunking long words is important, but it should be just one part of a wider literacy intervention. We also need to ensure that students have the foundational phonic and morphological knowledge that enables them to implement the chunking strategies. And, alongside specific chunking strategies, we need to develop students’ vocabulary, so that they can improve their chances of successfully decoding long words. And, of course, students need to read texts to develop their fluency, and to help them make sense of words in context.

As I’ve written previously, literacy interventions for adolescents should integrate knowledge from different domains. Reading long words is a great example of where different areas of knowledge come together to help with decoding and comprehension.

References

Devin M. Kearns (2020). Does English have useful syllable division patterns? Reading Research Quarterly

Susana Padeliadu and Sophia Giazitzidou (2018). A synthesis of research on reading fluency development: Study of eight meta-analyses. European Journal of Special Education Research.

Useful resources for teaching older students strategies to break up long words

LIfTT resources, particularly the following modules: Building Blocks of Words, Making Sense of English Spelling, and Chunking Words for Reading and Understanding.

Research-based routines for multisyllabic word reading with Jessica Toste and Brennan Chandler. Melissa and Lori Love Literacy podcast Episode 237.

Reading long words with Dr Devin Kearns. The Teaching Literacy Podcast Episode 34.

Devin M. Kearns, Cheryl P. Lyon and Shannon L. Kelley (2022). Structured literacy interventions for reading long words. In Structured Literacy Interventions: Teaching Students with Reading Difficulties Grades K–6 edited by Louise Spear-Swerling (The Guilford Press, New York).

Devin M. Kearns and Victoria M. Whaley (2019). Helping children with dyslexia read long words.

Providing Reading Intervention for Students in Grades 4-9 – Educator’s Practice Guide. Recommendation 1 in this guide gives suggestions for teaching students to divide multisyllabic words.