What are the specific literacy needs of adolescents, and how can we meet them?

Why do we need literacy interventions specifically designed for adolescents? In this blog post, I discuss the eight main ways in which the literacy needs of teens and tweens differ from those of younger pupils, and how to address those needs.

1. They have more diverse literacy needs

Each student’s literacy background will have different pieces missing.

I’ve found that one of the most challenging aspects of teaching older children and teenagers is that their needs are incredibly varied. This variation is even greater than for younger pupils, and at one level this can be explained simply because they’ve been alive longer! So, as well as any initial differences in abilities, for over 10 years these students will have been influenced by factors including:

Different home environments

Different levels of motivation

Different experiences in the classroom

Acquisition of different types of background knowledge.

The wide range of challenges faced by teenage learners has implications for literacy teaching. An intervention for secondary students has to be able to fill in any ‘missing pieces’, whether those gaps relate to phonics (the correspondences between sounds and letters), fluency, spelling, morphology (word structure), handwriting, punctuation, vocabulary, or comprehension.

2. They can be embarassed by primary-level resources

Adolescents may find it humiliating to use resources designed for young children.

I’ve come across many students at secondary school who struggle to read words of more than one-syllable, or who rely heavily on guessing based on a few initial letters. For example, complicate might be read as complaint, or dream as drama.

Lots of these students need an intervention that includes phonics. However, as most children learn phonics during the early years of primary school, phonics resources tend to be targeted at lower-primary pupils. Naturally, teens and tweens will feel embarrassed and demotivated if presented with babyish pictures or colourful plastic letters. They need resources that use pictures, formats, games and vocabulary that are appropriate for adolescents.

3. They need more challenging phonics resources

When I started teaching literacy, some of my students were frustrated that I was giving them phonics work that was too easy. And I was frustrated because I had carefully assessed their phonic knowledge in a nonsense word assessment, and I knew that they needed to learn the graphemes that I was teaching!

I realised that the difficulty arose because many of my students had wide ‘sight reading vocabulary’, even though they struggled with decoding. For example, a nonsense-word assessment would show that a student needed to learn the grapheme <ai>, but the student already recognised the words rain, Spain and snail by sight. For the <ai> grapheme, I found that the words entertain, dainty and traitor provided a more suitable level of challenge for most students in this age group.

Now that I’ve created resources with vocabulary at the appropriate level, students have to pay attention to the graphemes and decode the words systematically. Even though it’s more effort for them, they’re motivated because they feel that they’re making progress.

4. They need to read and understand long words

For some students, literacy difficulties will only become apparent at secondary school¹. Suddenly, they’re expected to read longer texts that contain unfamiliar vocabulary, including lots of complex words².

Reading long words requires specific skills, including a good knowledge of prefixes and suffixes, and the ability to break words into syllables. So, a literacy intervention for adolescents needs a strong emphasis on morphology, plus a systematic approach to teaching syllabification.

Many students who struggle with literacy will also have a relatively poor vocabulary, as they haven’t had much exposure to advanced vocabulary through reading. These students need to learn new vocabulary, which means they need repeated exposure to new words in contexts where they engage with word meaning. There are lots of practical suggestions for vocabulary teaching in the book Bringing Words to Life (reviewed here). I’ve built vocabulary development into my literacy teaching by creating sets of resources (worksheets, games and online activities) that repeat challenging words in tasks that require students to think about word meaning.

Etymology (word origins) is another pathway into understanding long words. I use activities that help students to look for etymological connections between words, and to link new vocabulary to familiar words. For example, television combines the Greek base tele- meaning “far”, with vision, which is derived from the Latin root videre meaning “to see”. These word-parts are easy to connect to meaning – a television enables you to see pictures from far away. Understanding these word-parts allow students to explore the connections with other words such as telephone, telescope and telepathy, or revision, supervision or visor.

I use this simple resource to help students learn the word phoneme by connecting the base <phone> to the concept of ‘sound’ using words that they already know (microphone, megaphone, telephone).

5. They need to understand complex ideas from longer texts

I come across lots of students who can decode individual words reasonably well, but find it slow and effortful to read long texts. These students haven’t attained reading fluency, and this can become a problem at secondary school because not only does vocabulary get more advanced, but so do the ideas that students are expected to understand from texts. Non-fluent readers use up so much ‘mental energy’ decoding the words on the page that they don’t have enough capacity left over to process the meaning of complex texts.

As fluency is necessary to fully participate in mainstream lessons, a literacy intervention for adolescents needs to include plenty of opportunities to practise reading challenging texts. Students should be given feedback to improve fluency and accuracy, and, ideally, the chance for repeated reading³.

6. They often need lots of practice

A few older pupils struggle to read because, for whatever reason, they’ve had major gaps in their education. But most pupils who struggle with literacy at secondary school are likely to have fallen behind because their brains find it difficult to process the written word, and they haven’t had the support they need to keep up with their peers.

Some of these students will have a diagnosis of dyslexia and others won’t. In either case, they are likely to need lots of practice to reach a level where they can process words quickly and easily. Therefore, students need access to lots of targeted activities to practise specific reading and spelling skills, so that they can retain what they have been taught and apply it to their own work.

7. They’re often keen to know how English spelling really works

After years of frustration at what they perceive as illogical English spellings, some older pupils and teenagers are genuinely enthusiastic about finding out about how the English language really works, so that they can finally catch up with – or even overtake – their peers.

These students need an intervention that doesn’t patronise them with ‘heart words’ and “it’s just another exception”, but actually explains how morphology, etymology and orthography (spelling patterns and rules) all work together to influence spelling.

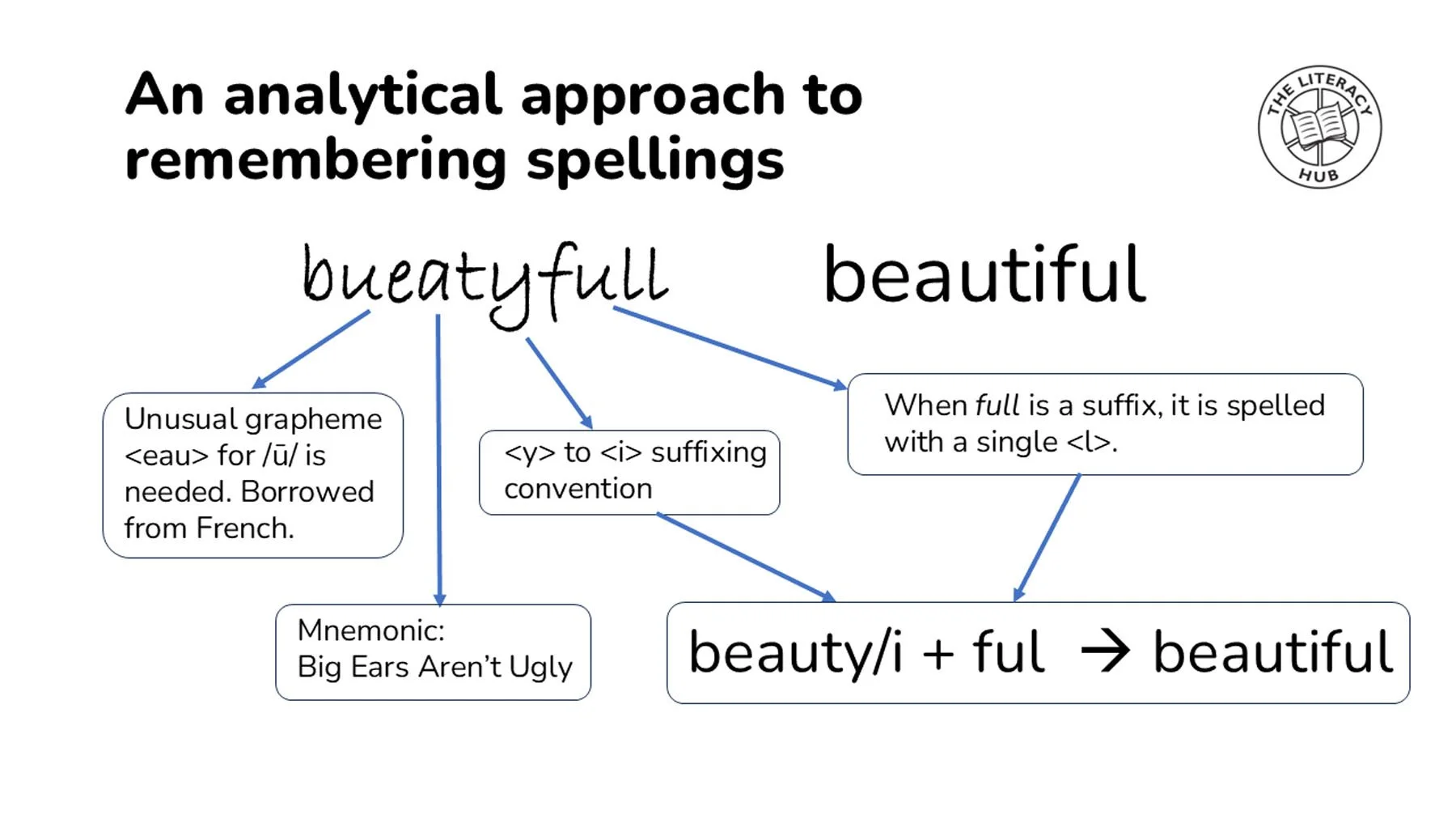

I’ve found that using an analytical approach that explains underlying principles and explores the real reasons for the ‘oddities’ of English is appealing to a lot of teenagers. They feel like they are being treated like adults learning a technical subject, rather than going back to primary school for catch-up lessons.

Spelling errors should be addressed in a targeted way using phonics, morphology, etymology or spelling conventions, as appropriate.

8. They need to integrate lots of skills quickly

While primary children have the opportunity to build up slowly from simpler to more complex words, secondary students need to start reading advanced words as soon as possible. This means they need an intervention that quickly gives them a range of ‘word attack’ skills. For all but the lowest-attaining students, it’s not appropriate for an intervention to focus just on phonics. Instead, an integrated approach is needed from early on. I like to provide students with an overview of ‘how words work’, and then teach different proportions of phonics, spelling (morphology and etymology), fluency or writing, as students’ needs dictate.

Conclusion: What should a literacy intervention for adolescents look like?

So how do these eight differences in student needs translate into what you should look for in a literacy intervention for adolescents? I think a successful literacy intervention for adolescents needs to:

Be wide-ranging and flexible – to cover the varied needs of students.

Not be patronising – resources need to be an appropriate format for older pupils.

Use challenging vocabulary – adolescents need work that requires them to use the knowledge and strategies that they have been taught.

Include specific strategies for decoding and understanding long words.

Include opportunities for (repeated) reading of challenging texts, with feedback.

Include loads of engaging resources that target specific reading and spelling skills.

Take an analytical approach to the English language.

Encourage students to integrate knowledge and skills from different areas (phonics, morphology, etymology, punctuation, comprehension) to decode and understand texts.

As a literacy support coach, I found it difficult to find resources that ticked all these boxes, so I’ve spent the last few years creating, trialling and optimising LIfTT, the Literacy Intervention for Teens and Tweens. If you’re interested in finding out more, please take a look at the literacy intervention page, or get in touch.

References

Hugh W. Catts, Donald Compton, J Bruce Tomblin and Mindy Sittner Bridges (2012). Prevalence and nature of late-emerging poor readers. Journal of Educational Psychology.

Nicola Dawson, Yaling Hsiao, Alvin Wei Min Tang, Nilanjana Banerji and Kate Nation (2023). Effects of target age and genre on morphological complexity in children’s reading material. Scientific Studies of Reading.

Susana Padeliadu and Sophia Giazitzidou (2018). A synthesis of research on reading fluency development: Study of eight meta-analyses. European Journal of Special Education Research.

Useful reading about teaching adolescent literacy

Thinking Reading: What Every Secondary Teacher Needs To Know About Reading by James and Dianne Murphy (reviewed here)

Providing Reading Intervention for Students in Grades 4-9 – Educator’s Practice Guide

Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction by Isabel L. Beck, Margaret G. McKeown, and Linda Kucan (reviewed here)